Dr. Hashimi: Officer Networks and Firearm Behaviors: Assessing the Social Transmission of Weapon-Use

Background

It is no secret that policing is group work – officers are assigned to beats/units, workgroups, and partnerships based on districts or specialized skills. Working in close contact, officers form tight bonds where they depend on one another for their safety and turn to one another for guidance and advice. Indeed, past work has argued that officers develop attitudes and form behaviors that align and are modeled after their peers. Though this list is not exhaustive, see Doreian & Conti (2017), Fagan & Geller (2015), Ouellet et al. (2019), Quispe-Torreblanca & Stewart (2019), Roithmayr (2016), and Savitz (1970) for examples. Our study extends on this line of work, drawing from network science to identify whether officers' relationships within a department shape their risk of firearm use. Specifically, we evaluate how exposure to colleagues with histories of firearm use shapes an officer’s likelihood of using their firearm during a use of force incident.

Data & Methodology

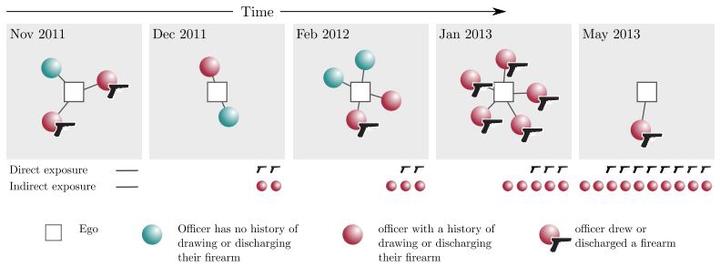

We rely on a statewide dataset of use of force incidents in New Jersey from 2012 to 2016. Each force report provides details of the nature of the incident, including whether a firearm was used (i.e., drawn, pointed, or discharged) and information on the officers involved in the incident. Because each force report in the database provides details of all officers named in the incident, we map the ties between officers who are co-named in the same force incident and then identify an officer’s exposure to colleagues with histories of using their firearms.

To test whether an officer’s peers shape their firearm use, we rely on a matched case-control design with conditional logistic regression and permutation tests to make inferences. Our approach matches officers who used their firearm with officers who did not use their firearm during the same force incident, directly comparing firearm and non-firearm using officers within the same environmental and situational contexts. With this approach, we can compare officers responding to the same calls, at the same time, with the same civilians. Within each force incident, the permutation procedure randomly shuffles which officers use their firearm and which do not, creating a permutation distribution whereby firearm use is independent of officer characteristics. For more on this method, check out this paper by Greg Ridgeway.

Findings

Our findings lead us to two major takeaways. First, officers with greater exposure to peers with histories of firearm use were less likely to draw, point, or discharge their own firearm during a force incident. In other words, officers exposed to a higher number of colleagues with histories of firearm incidents were less likely to engage in firearm use themselves. Second, many officer-related background features shape the likelihood of firearm use. White officers were less likely to use firearms during a force incident than non-White officers. In contrast, females, officers at the rank of “police officer,” and those with greater job experience were more likely to use their firearms during a force incident. However, this later effect tapered off over time. That is, as officers gain more experience, the risk of firearm use during a use of force incident declines.

Discussion

What does this mean? Well, our results counter socialization effects in a traditional sense, such that firearm use may not necessarily be a “learned” or “socially transmitted” behavior. Rather, officers embedded in use of force networks with a greater number of firearm-using peers are less likely to use their firearm during a force incident. With this in mind, we have to acknowledge that firearm use is an exceedingly rare event. And when it happens, using and discharging one’s firearm on the job has consequences that spill over beyond the officer pulling the trigger, impacting officers directly on the scene, the unit/squad, and the department more broadly. Indeed, high-profile firearm incidents have transformed departmental leadership and have led to resignations and turnover. In these contexts, firearm use may produce social and capital costs to officers, such as exclusion, loss of status, disciplinary actions (formal and informal), and risk-based suspect reactions. Thus, seeing one’s peer draw, point, or discharge their firearm may reshape an officer’s calculus of the potential costs and benefits of taking similar action.

Study Limits

These results should be interpreted within the limitations of the study. First, our network measures are bound to the peers with whom officers are co-named in a use of force incident, thus narrowing the lens through which we examine peer influence. Second, we rely on use of force incidents in one state. Although, we are able to compare officers' networks across large and small departments across five years, we are limited to data provided by departments in New Jersey. Relatedly, while these data are extensive and rare, it is administrative data with the limitations that come along with it (e.g., variations in reporting patterns and behaviors, missing and incomplete data). Third, we are unable to account for peer influence processes that could arise during the incident. In other words, the order of events within an incident can determine if force occurs and how it escalates, though, in the current study, we cannot tease out the causal order of peer influence at the time of the incident. Finally, our data do not establish causality but allow us to isolate time order by examining an officer’s exposure to weapon-prone colleagues before the current force incident and ruling out situational confounders.

Next Steps

Where do we go? We echo what many academics and practitioners call for: nationwide collection efforts that stem from better reporting habits. We rely on the Force Report compiled by NJ Advance Media through a series of public records requests. The fact that we have to rely on private agencies, independent efforts, or crowdsourced data to estimate these behaviors is problematic. The reluctance of agencies to provide these data are even more problematic. Data availability and transparency are often what lead to accountability. Yet, when we cannot systematically track what is going on, it makes understanding and assessing the problem difficult. In line with better data practices, we should continue to consider the importance of peers in the workplace. The study of peers is not new to our discipline; however, the use of social network analysis and imagery for understanding these interdependencies has been slower to gain traction within the policing environment. For exceptions, in addition to the few noted previously, also see Jain et al. (2022), Simpson & Kirk (2022), Wood et al. (2019), and Zhao & Papachristos (2020). We, along with others, continue to argue that how officers behave, how (and with who) they align their behaviors, and the attitudes they adopt can be linked to who they are surrounded by, whether that be their shift partners, workgroups, friends, or mentors in the workplace. Peers play a role in shaping behaviors and shifting cultures, and we need to continue to push the needle forward on the outcomes of these relations within the profession.

For more details, check out the full article in Journal of Quantitative Criminology. If you don’t have access, you can download a free preprint from Crimrxiv.